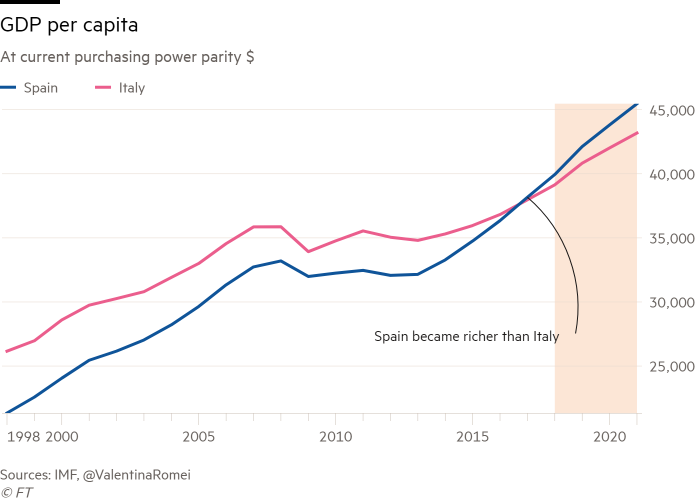

Decade of stagnation leaves Rome trailing in terms of output per head

Please use the sharing tools found via the email icon at the top of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach ofFT.comT&Csand Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.comto buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

https://www.ft.com/content/90d28bbc-43c2-11e8-803a-295c97e6fd0b

Spaniards have become richer than Italians — a heartening indication of Spain’s economic revival but a worrying sign for Italy, the eurozone’s third-largest economy, which is stuck in political gridlock. Spain’s per capita gross domestic product exceeded that of Italy in 2017, according to IMF data published this week that compare countries on a so-called “purchasing power parity” basis. The IMF also forecast that Spain would become 7 per cent richer than Italy over the next five years. A decade ago Italy was 10 per cent richer on the same basis. The data and forecasts show the sharply diverging fortunes of two countries that were severely hit by the eurozone economic crisis over the past decade. While Spain is now one of the fastest growing countries among leading EU economies, Italy remains an economic laggard. By 2023 some former Soviet bloc countries, including Slovakia and the Czech Republic, are also expected to become richer than Italy on a per capita basis, the IMF forecasts show. “It’s been since the 16th century that Italy and Spain keep overtaking each other — but they have something on us now,” said Carlo Alberto Carnevale Maffè, a professor at the school of management at Bocconi University in Milan. “Spain has been on a more robust and convincing growth trajectory than Italy since at least 2011, so this has been coming.”

Please use the sharing tools found via the email icon at the top of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.comT&Csand Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.comto buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

https://www.ft.com/content/90d28bbc-43c2-11e8-803a-295c97e6fd0b

Italy’s stagnation is one of the main causes of the country’s increasingly bitter political divisions, with the electorate losing faith in the ability of its traditional parties to create jobs and restore growth. Anti-establishment and protest parties emerged as the big winners of Italy’s inconclusive general election last month, where voters deserted more moderate centre-left and centre-right forces. Italy’s underperformance — and in particular any threat to its ability to service its debt, the largest in the eurozone after Greece’s relative to the size of the economy — is also seen as one of the biggest risks for the single-currency area. Without structural economic improvement Italy “continues to pose a latent threat to the euro area”, said Lieven Noppe, senior economist at KBC, in a recent note.