Happy Meskel!

Meskel [መስቀል mäsqäl], meaning Cross, is one of the major national and religious holidays in Ethiopia. Christians throughout the country celebrate Meskel to commemorate the finding of the True Cross used in the crucifixion of Jesus. This popular Feast of the Cross takes place on Meskerem 17 of the Ethiopian calendar, corresponding to September 27 in the Julian calendar (or September 28 during leap year).

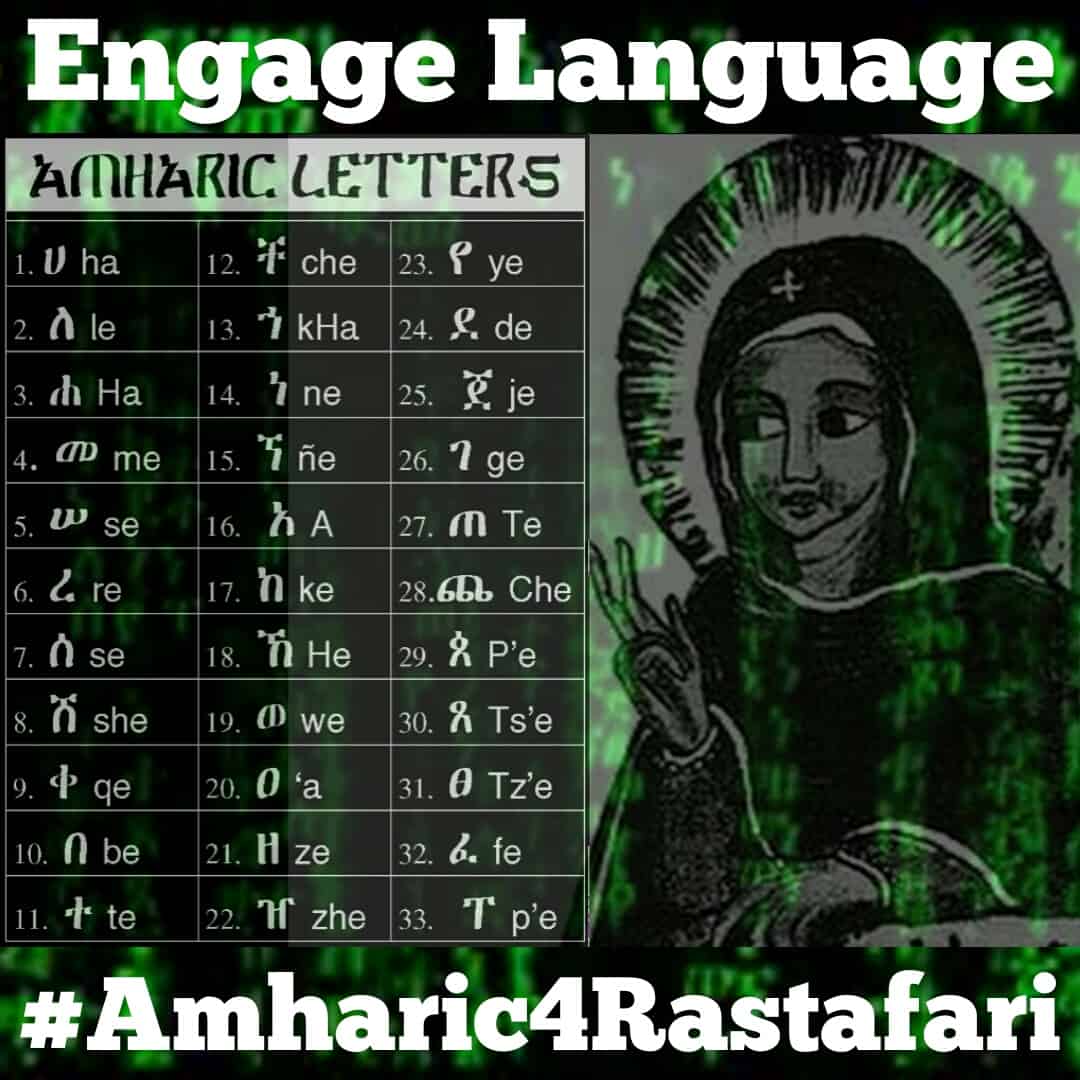

In rural communities, the preparation of the Feast starts several weeks in advance. On the Eve of Meskel, “Demera”, a bonfire in Amharic, takes place in the nation’s capital where people from diverse communities attend a lively event of religious chanting at Meskel Square. You might enjoy watching this video of Meskel drumming and celebration.

መስቀል Meskel Daises Aka Adey Abeba Flowers

The country is covered this time of year in the beautiful yellow flower, the meskel flowr.

It is widely believed that the True Cross was discovered by Saint Helena, the mother of the Roman Emperor Constantine, during a pilgrimage she made to Jerusalem in 326. A fragment of the Cross is said to be kept at an Orthodox church in Wolo region of northern Ethiopia.

Besides its religious aspect, Meskel is a special time of the year when families get together and urban dwellers visit their rural relatives. The immense participation of families, especially among the southern communities adds to its significance and beauty. Many Ethiopians use the occasion to promote peaceful coexistence, resolve personal conflicts, and enhance spiritual life.

In other Christian countries, there are various Feasts of the Cross all celebrating the Cross as an instrument of salvation according to their particular customs.

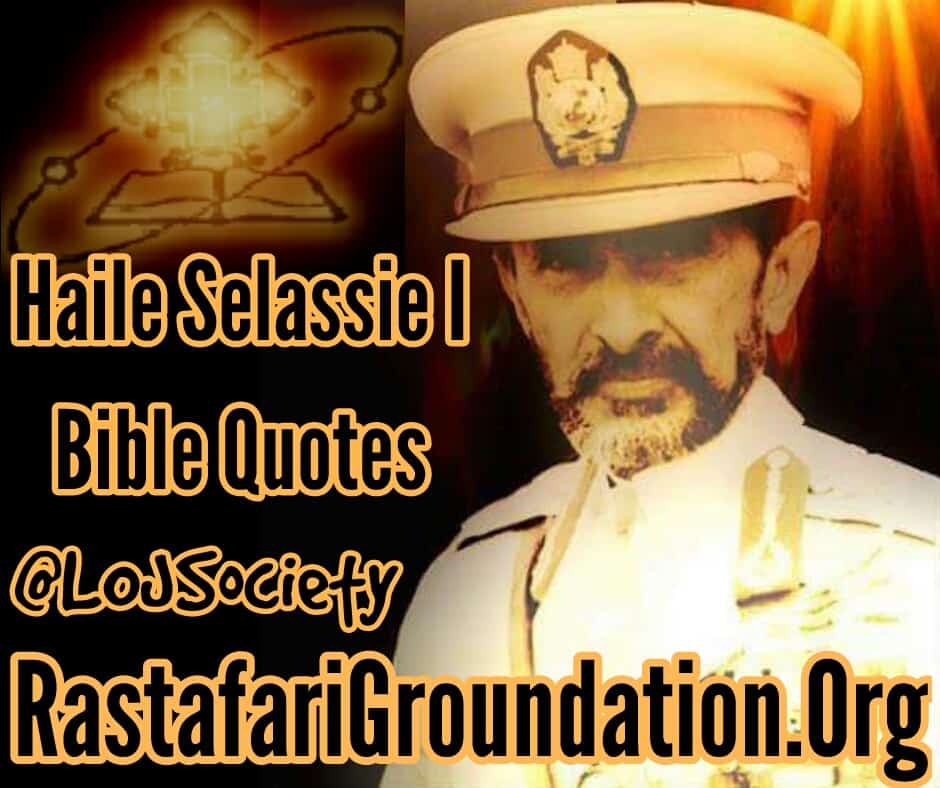

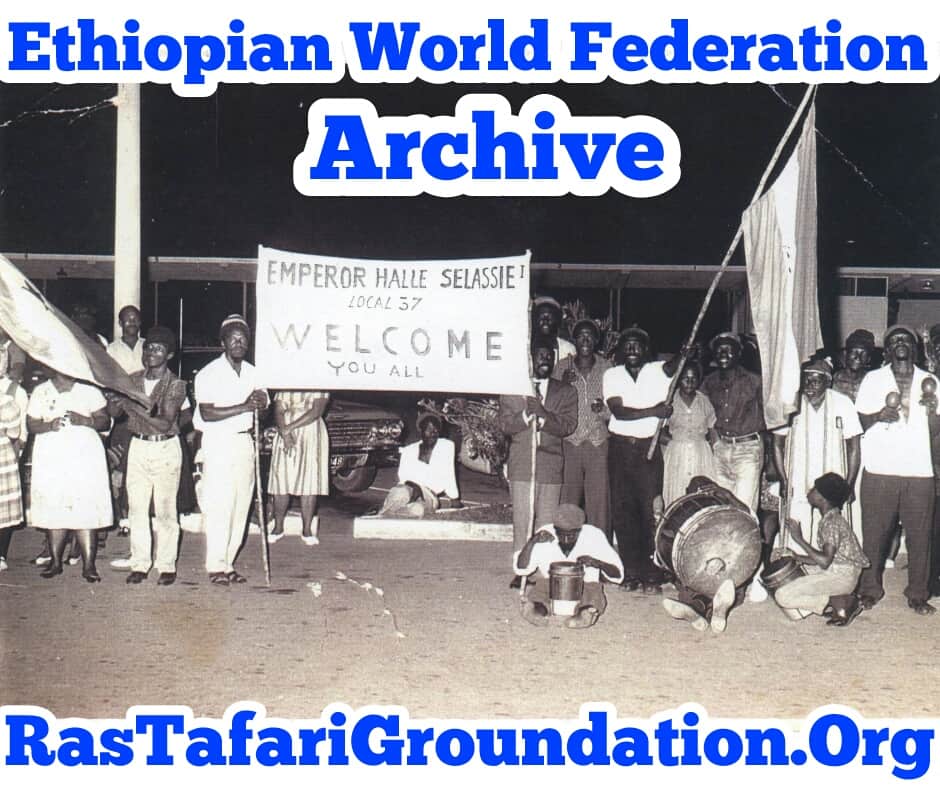

Emperor Haile Selassie attends Meskel, September 1968 | ቀዳማዊ ኃይለ ሥላሴ በመስቀል በአል መስከረም 1961 ዓ.ም.

MESKEL | LEGEND OF THE FINDING OF THE HOLY CROSS

The Legend of the Finding of the Cross (L.F.C.) developed in Jerusalem in the middle of the 4th cent. in connection with the pilgrim traffic that was then gathering momentum. The legend is widely spread across the whole Christian world, but enjoyed special popularity in the Orient, where it occurs in a variety of languages: Greek, Syriac, Arabic, Gééz, Armenian, Georgian and even Hebrew.

The standard version attributes the finding of the cross to the mother of Emperor Constantine (306– 37), Helena, who travelled to Jerusalem where she learned from a Jew (usually called Judas) that it was buried under a heap of earth. She had it removed, but found three crosses. In a miraculous way, it was eventually revealed which of them was Jesus’s: namely, the one that, in contact with a dead per- son, brought him or her back to life. Judas, who converted to Christianity changing his name into Cyriac (Gr. Kuriakovş, ‘The Lord’s one’), eventu- ally became bishop of Jerusalem.

There exist several Gééz versions of the Legend of the Finding of the Cross One of them is entitled Nägärä astärýayot mäsqälu Ÿabiy läýégziýénä wäýamlakénä Iyäsus

Kréstos amä 8 läţédar bämäwaŸélä Qwäsianiinos néguí Ÿabiy mähaymén ţer (‘The Story of the appearance of the great, life-giving Cross of our Lord and God Jesus Christ on 8 Òédar in the epoch of the great, believing and good king Con- stantin’). It is transmitted either in the Gädlä sämaŸétat, e.g., ms. BritLib Orient. 691 (15th cent.), or autonomously, e.g., BN Abb. 92 (15th– 16th cent.). The text in the homiliary EMML 1766 (14th cent.) seems to belong to a different redac- tion than that in the two previous mss. (published Guerrier – Grébaut 1925-26).

The Story has a composite structure. It features Empress Helena (Eth. Éleni) finding the Cross with the help of Judas, later called Cyriacus (Eth. Yéhuda Kirakos). Another narration of the same legend follows, an abbreviation of the Protonike Legend (known from the Syriac Abgar-Addai Legend), in which it is again Helena who takes the place of the legendary wife of Emperor Clau- dius. This is followed by a treatise on the Cross (containing inter alia the vision of Constantine before the battle with Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge), divided in two parts by the insertion of an abbreviated version of the Legend of the Finding of the Cross.

The Story has a sequel in the “Acts and Mar- tyrdom of Bishop Cyriacus” (Gädl wäsémŸ zäkirakos pappas), which is also transmitted in the Gädlä sämaŸétat. Judas, who helped Helena find the Cross, became a Christian, but died as martyr, together with his mother, during the reign of Julian the Apostate (361–63).

8 Òédar [14 November is the day on which, according to the Sénkéssar, “the Cross ap- peared to Constantine” (ColSyn VIII, 272–73; BudSaint 222). Thus, the “Story of the appear- ance of the Cross” was read in commemoration of that event, which also shows why it was given the present title.

Still another version, a shorter one, can be found in the Täýammérä Maryam. It tells the Story of Theodoxia (Eth. Täwdokséya) or, ac- cording to other manuscripts, Theodosia (Eth. Täwdoséya), the daughter of Empress Helena, who prayed to the Holy Virgin that she might see the grave of Jesus in Jerusalem, and the Holy Cross. Eventually, Jesus appeared to her and told her to go to the Holy City together with her brother, Emperor Constantine, in order to find the Cross. Once she had found the Cross, her name would be changed into that of her mother. In this way, the person who finds the Cross is still a Helena. Such legend is apparently derived from the 7th-cent. Coptic legend on Eudoxia and her finding of Jesus’ sepulchre. Since no transla- tion of that into GéCéz is known, the Coptic tra- dition probably reached Ethiopia in oral form. The earliest GéCéz manuscripts containing it are from the 16th cent., whereas the Täýammérä Maryam were translated already in the 15th cent.– the redaction of the Story of Theodoxia there- fore dates to ca. 1500 A.D.

The finding of the Cross is also mentioned sev- eral times in the Sénkéssar: for instance in the reading for 16 Mäskäräm [23 September, on which the construction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is commemorated. In this passage it is bishop Macarius, and not Judas, who helps Hele- na to find the Cross (ColSyn VI, 418–21; BudSaint 55ff.) on 17 Mäskäräm [24 September, i.e. the Mäsqäl Festival (ColSyn VI, 426f. and BudSaint 59f., resp.). Here Helena is told to have forced the Jews to remove the heap of rubbish amassed over the period of 200 years that buried the Cross. This story is repeated in the reading for 10 Mäggabit [16 March (ColSyn XI, 334–37; BudSaint 684ff.). The ÷Heraclius legend is also tracable in the reading for 9 Génbot [14 May commemorat- ing Helena, who is said to be a native of Edessa. She discovers the Cross with the help of bishop Macarius (ColSyn XII, 228–31). Though the Cross has the titulus, the queen wishes to see a miracle, which takes place when a dead man is touched with the Cross.

There are also other, shorter mentions of the finding of the Cross in the Sénkéssar: on the day of the commemoration of Helena, 18 Mäskäräm [25 September (ColSyn VI, 436); on the feast of St. Cyriacus, who informed Helena as to where the Cross was to be found, 5 Téqémt [12 Oc- tober (ColSyn VII, 18–21), on the day of the commemoration of Constantine, who is said to have sent his mother to search for the Cross, 28 Mäggabit [3 April (ColSyn VI, 432f.).

There is one more text that includes the L.F.C., unpublished and known only from a description of the unique manuscript in which it is preserved (BritLib Orient. 698, s. WrBritMus 181). Here the Legend of the Finding of the Cross is embedded in a totally fictitious his- tory of the Roman empire, the rulers of which are called by such names as Inýidän, Alýadäd, Agdér and Yayas. In due course, Helena becomes the empress, whereas Constantine appears as her successor, being the eldest of her 29 sons. Helena goes in search of the Cross, and Cyriacus plays his role here too.

Source:

Encyclopaedia-Aethiopica

Haile Selassie I at Religious Ceremony of Meskel