Whether you like it or not, the move toward renewable power is a certainty in the energy sector.

But as we’ve discussed here in Oil & Energy Investor before, there are significant impediments to a continued and robust adoption of renewable energy.

The primary roadblock is cost – but not in the way you might think…

The expenses involved in generating solar and wind power have actually declined significantly over the past several years.

Additionally, these days we’re talking more about “grid parity” – when renewables match the cost of generating and putting electricity on the wider grid.

In many parts of the U.S., solar and wind have improved to a point where they cost about the same as more traditional sources of power.

As loyal readers saw last September, this improvement has resulted in solar reaching a federal milestone much earlier than expected.

But the issue hardly ends there…

A few weeks ago, we talked about the strange situation in Germany, where consumers have actually been paid to use electricity.

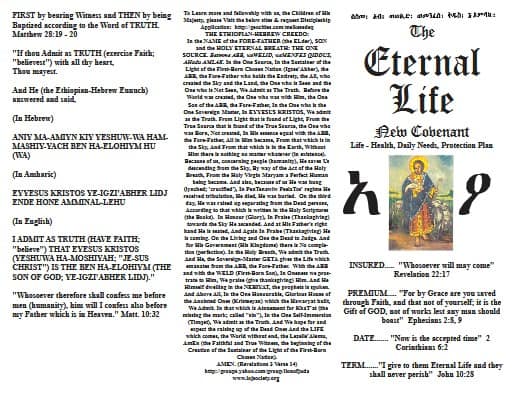

On 140 acres of unused land on Nellis Air Force Base, Nev., 70,000 solar panels are part of a solar photovoltaic array that will generate 15 megawatts of solar power for the base. (U.S. Air Force photo/Airman 1st Class Nadine Y. Barclay)

That is one wrinkle in the new “ceiling debate” on how far (and how fast) renewables can be expected to increase.

But the problem has always been balancing when the electricity is generated with when it’s needed.

Given the lack of significant capacity to store electricity, it must largely be consumed as it’s produced. To ensure even peak demand can be met, this results in excess generating capacity.

In other words, the more electrical generation in places like the U.S. and Western Europe, the more pressure there is on bottom lines. In the power generation sector, this is measured using “return on kilowatt hour produced.”

As this situation becomes more acute, it will progressively act as a barrier to the rapid expansion of renewables, with two important caveats…

Developing Countries Won’t Give Up on Coal

First, much of the world is in dire need of ever more electricity.

Whereas in the developed world, overall demand is largely flat, that’s not the case for the over 70% of the globe’s population living in developing countries.

Among other things, the move to solar makes a lot of sense in places like the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia where the climate bodes well for maximum sunshine.

In specific areas in these regions, using more renewables allows countries to export – rather than burn – oil and even coal.

That’s a pretty enticing way to increase your country’s revenue.

Therefore, limiting the conversation to the developed OECD countries skews the picture somewhat.

Second, the next wave of solar and wind advances in places like the U.S. will be a replacement for existing power generation, rather than an addition.

In this case, it’s less about increasing overall generating capacity as it is a matter of moving production from coal to renewable energy.

Now, the change from coal to natural gas has been a hot topic of conversation over the past decade. An additional move away from gas to renewables is less likely.

For that matter, while declining in its percentage of the generating sector, the further drop in coal is probably going to be leveling off over the next several years.

There are dual considerations here: the overall age of the generating plants, and the existence of a positive cost differential in several parts of the country.

That’s why I expect the rise of a new kind of power generation…

Why Renewables Will Need Natural Gas

I’m talking about so-called co-fueled facilities.

Unlike the recent past, where “co-fueled” meant combining coal and natural gas, this time around we’re going to see a combination of renewables and gas.

In other words, solar and wind are attached at the upstream harvesting stage.

This does not solve the excess power problem, but it would allow for a more efficient distribution in the energy souring on the production side.

However, I see another main contributor – and a more difficult barrier to overcome – to the renewable ceiling.

This is the reality of intermittent power.

Solar and wind are not guaranteed power sources. The sun doesn’t always shine nor does the wind always blow.

Therefore, with the current state of battery technology, there cannot be intentional overproduction during favorable times.

Each new unit of solar or wind added to the grid requires the availability of backup power sources.

That means either alternative co-fueling with other renewables (e.g., biofuel, geothermal, tidal), which is an approach not likely to be in wide use medium-term, or maintaining traditional sources for duplicate power availability.

And both considerations are not matters that solar and wind advocates want to think about for one very vexing reason:

Each effectively adds to the real cost of renewable power production.

Again, the crux is a breakthrough in battery technology. If electricity can be stored in significant amounts, the need to reduce profit margins by paying for the use of or for backup generation could be substantially reduced.

Encouragingly, there are some developments here in focused applications in providing storage for localized applications.

One of these developments is a Tesla joint venture in Sothern California that has shown some upside, as we’ve discussed before.

ereBut the real test comes from the ability to scale batteries for larger use.

A recent project (again by Tesla) in South Australia may be the first stage here.

Nonetheless, everything points to the next generation of battery advances being able to successfully scale.

I’ve already presented some of the more encouraging indications in past issues – go here and here to see them.

Now, I may be guilty of overusing the “Grail” analogy in the past.

But the truth is something that looks very much like the “Holy Grail” for battery technology is fast approaching.

Nothing will ever be the same (for energy markets, at least).

link to @

https://oilandenergyinvestor.com/2018/01/the-one-thing-keeping-solar-and-wind-from-taking-over/?oei_subscribe=complete&email=djmims14%40yahoo.com